Technical Analysis of the Environmental Impacts of the Puerto Barú, Panama Port Project

Prepared for:

Environmental Advocacy Center of Panama (CIAM)

Panamanian Center for Studies and Social Action Association (CEASPA)

Adopt the Forest Panama Association (ADOPTA BOSQUE)

Foundation for Integral Development, Community, and Conservation of

Ecosystems in Panama (FUNDICCEP)

Panacetacea Panama Foundation

Panama Primates Project

Prepared by:

Lynker

December 6th, 2024

Puerto Barú Independent Assessment

December 6th, 2024

Executive Summary

Lynker conducted an independent scientific review of environmental claims related to the proposed Puerto Barú project near David, Panama. We examined the Environmental Impact Study (EIS) and focused on assessing the potential impacts from construction and ongoing port operations to the mangrove forest and nearby protected areas, which include numerous coral reefs, abundant marine wildlife, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

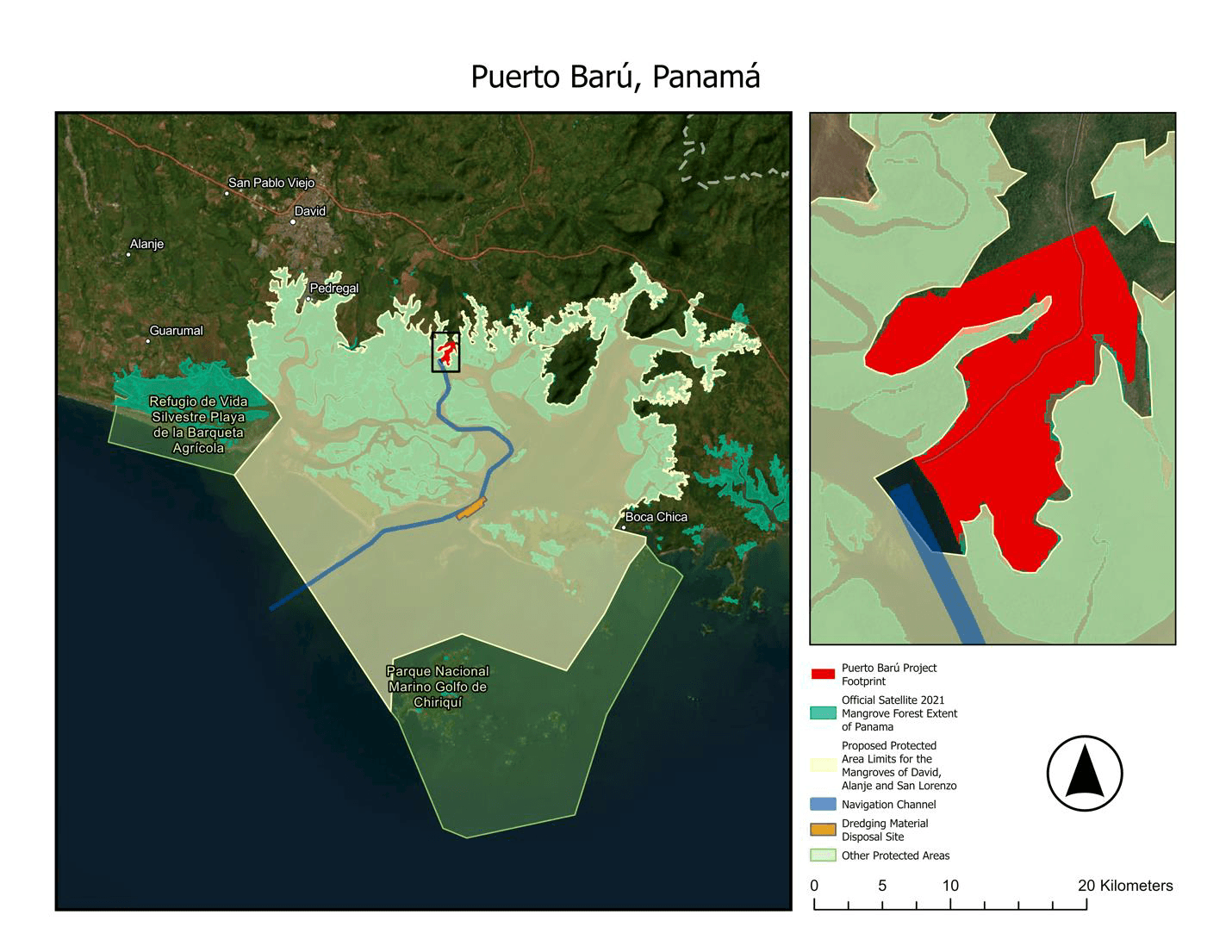

The developers claim that no mangroves will be affected by the construction and operations of Puerto Barú. Our analysis shows that the port complex footprint directly encroaches on about 30,800 square meters of mangroves (Figure 1) and that there is insufficient evidence to support the assertion that these nearby mangroves won’t be indirectly impacted by changes in hydrology, sedimentation, and pollution at and near the port complex. Our review also found that the developer’s frequently misrepresented distances to Coiba Island National Park and proposed inadequate solutions for mitigating impacts from increased vessel traffic.

Of greater concern, however, is the potential for significant and long-lasting negative impacts from dredging on mangroves and other nearby sensitive habitats. Peer-reviewed scientific studies indicate that dredging harms both mangroves and coral reefs by reducing light penetration and oxygen availability, clogging mangrove roots, disrupting seedling establishment, and smothering coral reefs with suspended sediments. In a case study from India, Azeez et al. (2022) found that due to the mobilization of fine sediments by tidal currents, the optimal location for the dredging dump site was 18–20 kilometers offshore in waters at least 20 meters deep. In contrast, the proposed Puerto Barú sediment disposal site is located within the estuary, where tidal currents would be expected to be strongest. Developers assert that despite this, dredging will be non invasive and that sediment plumes won't reach mangroves, which are a legally protected species in Panama. Yet, our review found that the sediment dispersion modeling on which this assessment is based failed to follow best scientific modeling practices for simulating the fate and transport of fine sediments like those present in the project area.

Overall, our assessment identifies significant shortcomings in the Puerto Barú EIS. Developers’ claims often lack evidence or misrepresent potential impacts on ecosystems protected under Law 304 of May 31, 2022 — legislation that safeguards coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds, all critical to Panama’s environmental health. Inadequate assessment of fine sediment dispersion, proximity to key protected areas, and increased marine traffic through the Gulf of Chiriquí and the David mangrove forest raises concerns about potential violations of this law and irreversible environmental damage, especially given Panama’s history of policy implementation gaps linked to high mangrove loss (Chamberland-Fontaine et al., 2022). Fine sediment dispersion from dredging operations could degrade water quality, harm coral reefs, and damage mangroves, while increased marine traffic may fragment habitats, cause pollution, and threaten marine species, undermining the ecological health of protected areas and associated habitats. Based on these findings, we recommend exploring alternative sites that mitigate these environmental risks while still supporting economic development opportunities in the David region of Panama.

Introduction

Lynker conducted an independent scientific review of the environmental and socio-economic claims made regarding the proposed Puerto Barú project, on the northwest coast of Panama near David (Figure 1). This memorandum presents our assessment of key claims and assesses their validity within the context of the Estudio de Impacto Ambiental Categoría III (EIA), its machine translated Environmental Impact Study (EIS) in English, and other publicly available documents such as the project website. The Puerto Barú developers presented their claims both in the EIA, on the project website, and in the document entitled Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project.

We provide here our evidence-based assessments of these claims, including counter evidence and arguments where needed.

Figure 1: The proposed Puerto Barú project footprint (red), navigational channel (blue), and dredging material disposal site (orange). The 2021 Mangrove Forest Extent (dark green) from Panama’s Ministry of the Environment, MiAmbiente, is a satellite-based land cover data product. The Proposed Limits for the Protected Area of the David mangroves (MiAmbiente, 2024) and other nearby protected areas are in the shaded yellow and light green polygons, respectively.

Review of Environmental Claims and Impacts

1. Mangrove Conservation Areas and Potential Impacts

Developer's Claims

- The project proposes to dedicate over 25% of its private land to mangrove conservation, including establishing an ecological corridor, buffer zone, botanical garden, and protection forests. (Source: Puerto Barú website)

- The developers state that no mangroves exist within the project boundaries and that none will be affected by the construction. (Source: EIS)

Technical Assessment

Potential Mangrove Impacts from Port Complex

The EIS provides detailed mapping of vegetation, topography, and the proposed project footprint, indicating that the port complex will be constructed on degraded land above the tidal level where mangroves do not naturally grow. While this mapping includes plans for ecological corridors and buffer zones (e.g., Fig 01.1 in the EIS Executive Summary), concerns remain regarding potential indirect impacts on nearby mangrove ecosystems, particularly related to changes in hydrology, sedimentation, and pollution resulting from construction and port operations. A vegetation map (P MB-03, EIS Executive Summary, p. 104) depicts the current vegetation at the port complex project area. This mapping indicates that the project footprint will traverse (boundary overlap) into the Manglares de David (David Mangrove Forest), a species protected under Law 304 from May 31, 2022 (Panama, 2022), which explicitly recognizes “the conservation of coral reefs, their associated ecosystems [i.e., mangroves], and species is of public interest and essential to guarantee the right to a healthy environment for all inhabitants”.

To verify the port complex’s overlap with the mangroves, we first calculated the mangrove forest extent within the proposed project footprint using the Panama’s Forest Cover and Land Use dataset for 2021 developed by Panama’s Ministry of the Environment (Ministerio de Ambiente de Panamá) from satellite imagery. We then delineated the port complex footprint from the coordinates in the EIS document (EIS Annex 26, pp. 2722-2726). From these two layers, our geospatial calculations estimate that the port complex will encroach upon approximately 30,800 m2 of the David mangroves. In Section 7.1 of the EIS (p. 767) it is noted that 5.74% of the surface area of the project footprint is covered by mangrove, but that those would not be impacted. No precise area of mangrove extent within the project footprint is provided. Our findings validate the EIS mapping showing encroachment of the project area on the David mangroves, but we question whether sufficient mitigation measures have been taken to address the very low reception capacity of mangroves to the clearing of vegetation (Section 9.1.2 of the EIS, p.953).

Our review of this evidence suggests that the EIS does not sufficiently address how construction activities, increased marine traffic, or other port infrastructure might directly or indirectly impact mangrove ecosystems, and is generally dismissive of these potential impacts, despite claiming that the environmental viability of the project is “highly corroborated” (EIS Executive Summary, Chapter XII, p. 4). Furthermore, these conclusions within the EIS are contrary to published scientific research, which indicates that impacts to mangroves from increased sedimentation and pollution are likely (e.g., Ellison, 1999; Thampanya et al., 2002; Maiti, 2013). Without more comprehensive coastal hydrodynamic, sediment dispersal and fate, and water quality modeling, our findings suggest that the developer has not sufficiently demonstrated that these ecosystems will remain unaffected by port construction and operations. In other words, there is, without a doubt, a threat of serious or irreversible damage to the mangroves. The combination of these factors raises concerns about the preservation of critical ecosystem functions and the enforcement of environmental safeguards under Law 304 of May 31, 2022 (Panama, 2022).

Potential Mangrove Impacts from the Navigational Channel

The proposed navigational channel, which traverses the interior of the David mangrove forest and will require significant dredging, is likely to have more widespread and consequential negative impacts than the direct impacts from the port complex. Key risks include smothering mangroves by the sediments suspended by dredging activities (Ellison, 1999; Section 2 of this memorandum), the accidental discharge of pollutants and contaminants from shipping traffic, and the possibility of subaqueous slope failure following dredging (e.g., Alhaddad, 2024) resulting in unintended widening of the navigational channel.

The EIS and Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project specify that the “the navigation channel that will give ships access to the port maintains about 19 km of its length within the protection area, since they are waters of the estuary associated with mangroves’’ (Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project, p. 7). Project plans specify that the channel will be dredged from its current depth of 7.5 m (mean low water springs; MLWS) to a depth of 11 m along the width and length of the alignment and up to 12 m at the site of the dock (Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project, p.7). The EIS also delineates a dredging materials dumping site towards the outlet of the estuary near the outer extent of the David Mangroves (EIS Executive Summary, p.204; Figure 1, orange polygon).

As discussed further in Section 2, the proposed initial and maintenance dredging activities are highly likely to suspend significant concentrations of fine sediment in the water column, at which point the horizontal transportation of these sediments by ocean and tidal currents becomes feasible. These suspended sediments from dredging can have a significant negative ecological impact on mangroves, including:

- Reduced Light Penetration: Suspended sediments cloud the water, blocking sunlight from reaching mangrove roots and leaves. This limits photosynthesis, slowing down growth and development (Alongi, 2008, Ellison and Farnsworth 1993).

- Clogged Roots: Sediments can settle on the aerial roots of mangroves, blocking their ability to take in oxygen. This can suffocate the roots and lead to tree death (Alongi, 2003, Azeez et al. (2022)

- Disruption of seedling establishment: Sediment deposition can bury mangrove seedlings, hindering their ability to germinate and grow (Ellison, 1999; He et al., 2022; Thampanya et al., 2002).

- Habitat Disruption: Dredging can disturb the delicate balance of the mangrove ecosystem, affecting the organisms that live in and around the mangroves, such as fish, crabs, and birds (Alongi, 2002 and 2003).

- Increased Salinity: Dredging can alter water flow patterns, leading to increased salinity in the mangrove environment. This can stress the mangroves and make them more susceptible to other stressors such as inter specie competition, tolerance levels and affect their growth (Smith, 1992 and Alongi, 2008).

Given the proximity of the navigational channel through the mangrove forest and the known impacts of suspended sediments, our review of the EIS reveals significant shortcomings in their assessment of the potential impacts of dredging on the mangrove ecosystem. While the EIS acknowledges the importance of grain size in understanding sediment plumes — e.g., stating that "sand and fines occupy a high percentage of the texture" (EIS, pp. 431, 434) — it presents conflicting assessments. For instance, Table 9.15 (EIS, COD N-FG-05, p. 1195) indicates a severe diffuse impact “due to the duration and continuity” of sediment transport alteration (i.e., dredging), yet elsewhere the EIS suggests soil loss from dredging is of low intensity (EIS, p. 1138). These contradictions raise concerns about the reliability of the impact assessments.

Our analysis suggests that the mitigation measures proposed in the EIS to minimize sediment dispersion impacts are insufficient and that negative impacts to the mangroves closest to the proposed dredging areas are highly likely. One mitigation measure discussed in the EIS is the use of "water turbidity rest windows" at the dredged material unloading site, which the developers claim will allow for greater than 4 hours of rest between dredge boats (EIS Executive Summary, p. 122 123). In a recent study in India, scientists found that dredging sediment plumes are strong controlled by tidal currents and can travel distances of 8 km, suggesting that an optimal sediment deposition site would be 18-20 km offshore at depths greater than 20 m (Azeez et al. 2022). Given the proposed location of the dumping site within the mangrove forest at the mouth of the estuary with strong tidal currents, our findings suggest that the water turbidity rest window is an ineffective strategy to counter risks of mangrove smothering.

In Law 304 of May 31, 2022, Article 20 states: “It is prohibited to throw, dump, pour or deposit non hazardous, hazardous and special handling waste, materials or solid waste, as well as hazardous liquid waste, in natural and artificial waterways, streams, reefs and coral communities, seagrass beds and mangroves.” (Panama, 2022). To evaluate the potential impacts of sediment dispersion on the nearby protected areas and mangrove forests, and whether dumping of dredged materials is compliant with environmental protections, it is important to understand local species distributions. Yet, our review of the EIS found a lack of detailed species distribution and sensitivity mapping. For example, species like Avicennia and Rhizophora have varying sensitivities to sediment burial, with significant mortality rates at certain sediment depths (Thampanya et al., 2002). Without comprehensive mapping, the EIS cannot accurately predict or mitigate these impacts, leaving vulnerable species at risk and raising questions about compliance with legal protections to key species.

While the EIS acknowledges negative effects such as fragmentation of ecosystem connectivity and disturbance of critical habitats during construction and operation (EIS, Table 9.8, p. 1023), it minimizes potential lasting impacts on resident organisms and habitats by mentioning only "transitory fragmentation" due to dredging and overlooking long-term effects on benthic organisms and tidal channels. The EIS asserts that critical habitats "may be disturbed, although not modified," neglecting the potential for lasting detrimental effects. Critical natural habitats, including significant mangrove areas along the canal (EIS, Table 9.11, p. 1068), are confirmed in the EIS, yet vulnerable species like the mangrove cockle (Anadara tuberculosa), which depend on mangrove roots, would be adversely affected by root clogging. The EIS claims shrimp larvae won't be affected because the mangroves "will not be touched" (EIS, p. 2877), but this overlooks indirect impacts of sedimentation on root systems and dependent organisms. Although the EIS recognizes the mangrove ecosystem as the best-preserved in the area and emphasizes its critical habitat status due to the interconnection of components (“entire system must be considered as a critical habitat, given the interconnection and interdependence that exists between its components” EIS, p. 755), it doesn't adequately consider how dredging could disturb this balance. Mangrove ecosystems are dynamic (Alongi, 2009), and understanding all components of the system is essential for accurate impact assessments (Ellison, 2021). The lack of long-term data on mangrove health undermines the EIS's ability to claim that impacts will be minimal or transitory.

Finally, another key factor influencing mangrove zonation and species composition is salinity (Smith, 1992; Alongi, 2008). The EIS does include salinity observations, but these are limited to a single station (EIS, 5.2.7, p. 1641). Post-dredge models predict significant changes in salinity patterns, with a greater range within the estuary and increased salinity in the narrowest zones (EIS, 6.4.1.2.9, p. 1723). Each mangrove species has its own salinity tolerance range (Lugo and Snedaker, 1974), and alterations could reduce diversity and impact animal zonation. The EIS does not adequately address how these changes could affect the mangrove ecosystem's structure and function.

In conclusion, the EIS has significant shortcomings in its assessment of the potential impacts of dredging on the mangrove ecosystem. It provides inconsistent analyses of sediment transport impacts, lacks adequate mitigation measures, omits detailed species-specific assessments, and does not sufficiently consider critical factors like salinity changes. These gaps suggest that the EIS does not fully address the environmental risks associated with the proposed project. Even without direct physical alteration, dredging activities for the navigational channel are likely to have detrimental effects on the mangrove ecosystem due to sedimentation, changes in salinity, and disruption of ecological connectivity.

2. Navigational Channel Dredging and Sediment Dispersion

Developer's Claims

- Dredging will deepen a natural riverbed using non-invasive procedures (e.g., sweep dredging) that remove only clay, silt, and sand. (Source: EIS)

- The dredged material generates a dispersion plume that does not reach mangroves. (Source: EIS; Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project)

- No dredging will occur within 50 meters of the riverbank, ensuring mangroves are protected. (Source: EIS)

- Sedimentary material predominantly settles to the bottom, causing little alteration to the marine habitat. (Source: EIS)

- The project will have no relevant effect on Coiba Island National Park. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project)

Technical Assessment

Our review of the coastal hydrodynamic model used for simulating sediment dispersion and described in the EIS found that the modeling approach applied by the developer’s consultants failed to follow best scientific modeling practices (e.g., Aijaz et al., 2013; NIRAS, 2021). The MIKE 21 ST FM sediment transport model used for the sedimentation analysis (Warren et al., 1992; see Section 6.2.1 and Fig. 39 in Annex 3 of the EIA) is designed for sand and coarse silt fractions on the bed, not fine sediments suspended in the water column from dredging. This model cannot accurately simulate the transport, dispersal, or fate of fine sediments introduced higher in the water column as the result of fine sediments spill during dredging operations. A more technically defensible approach would have been to use the Mud Transport module of the MIKE 21 FM modeling suite, which is better suited for analyzing the behavior of fine suspended sediments -- critical in tidal regimes (Truong et al., 2021). At a minimum, a similar level of detailed sediment plume modeling as in the study by Azeez et al. (2022) using the FVCOM model should have been completed for the Puerto Barú EIS. This significant oversight casts doubt onto the EIS’ conclusions regarding the minimal impact of fine sediment dispersion during dredging and disposal on nearby mangroves and protected areas.

Without the use of appropriate modeling techniques, claims about sediment plume behavior and its effects on adjacent ecosystems remain unsupported. The documented presence of fine silt and clay in the sediment samples and cores suggests that the coastal hydrodynamic modeling has been inappropriately applied and that the conclusions of the EIS with regards to potential impacts from dredging are questionable. With the large volume (over 9 million cubic meters) of dredging, the spilling of fine sediments during dredging and disposal operations will unavoidably increase suspended sediment loads, water turbidity, and fine sediment deposition in sheltered areas potentially impacting the nearby mangrove forests and local marine life. The proximity of the navigational channel to nearby sensitive protected areas (Figure 1) warrants further independent review.

Impacts on Protected Areas

The nearby protected areas like Isla Parida in the Parque Nacional Marino Golfo de Chiriquí (Figure 1) likely face greater risk from sediment plumes related to dredging and disposal operations, though these potential impacts remain inadequately assessed by the current modeling studies. In contrast, the EIS and supporting documents are likely correct in determining that the more distant Coiba Island National Park is unlikely to be directly impacted, but this should still be verified through more comprehensive sediment dispersion modeling.

Additional Considerations

Dredged sediments are described in the EIS as mainly consisting of sand and silt fractions. This statement is contradicted by the last paragraph on Page 546 of the EIA – Conclusiones and by Cuadro 6.68 Matriz sedimentaria de la zona de estudio. The bed sediment samples collected in support of the numerical model in Annex 3 of the EIA (Modelamiento Matemático de Sedimentación Canal Puerto Barú) also show significant presence of fine sediments (fine silt and clay fractions, see Figs. 36 and 37 in Annex 3). Similar results can be seen from the results of borehole samples and analyses presented in Annexes 7 y 8 (Geotecnia Marítima - Tecnilab S.A. - Rio Chiriquí Nuevo y Muelle, respectively).

The two dredging methods adopted for the project, as described in Section 5.4.2.2 of the EIA (p. 302-320), involve the use of two Trailer Suction Hopper Dredgers (TSHD) and a Backhoe Dredger (BHD). Sediment spill percentages from TSHD have been estimated as 3% (NIRAS, 2012) to 5% (Azeez at el., 2022) but could be even higher if overflow from the split barges is allowed. Spill rates are even higher for BHD: NIRAS (2012) estimates 5% of sediment spill if a clamshell bucket is used. Figure 5.91 in the EIS seem to imply that dredgers with open buckets will be used; if that is indeed the case, significantly larger rates of sediment spill should be expected, both when sediments get excavated from the local bed as while the bucket is pulled up along the water column.

Bernard (1978) synthesized the results of eight research studies into sediment resuspension and turbidity levels near various dredging sites in the United States. He concludes that water-column turbidity generated by dredging operations is usually restricted to the vicinity of the operation and decreases rapidly with increasing distance from the dredger. The following findings in Bernard (1978) are relevant for the Puerto Barú project:

- Grab (Clamshell): maximum concentrations of suspended solids within 50 to 100 m from the dredging site will be less than about 200 mg/l; the visible plume will be about 300 m long at the surface and approximately 500 m near the bottom; maximum concentrations will decrease rapidly to background values within 500 m

- Hopper: during overflow operations, turbidity plumes with concentrations of 200 to 300 mg/l may extend behind the dredge for distances up to 1,200 m; without overflow the concentrations are considerably smaller (factor 3 to 5); near-bottom concentrations of 1 to 2 gr/l are generated near the suction heads.

Based on Bernard’s findings, it can be reasonably assessed that the impact of the dredging plume will extend well beyond the 50 m buffer zone described in the EIS, especially if a dredger with an open bucket is used in the port basin area. The plumes are highly like to have a detrimental impact on the mangroves and the local marine life, unless sediment monitoring and management measures are carefully designed and carried out during the dredging operations.

Conclusions on Dredging and Sediment Dispersion Modeling

Documented presence of fine sediments in the dredging region exists. These fine sediments (i.e., fine silt and clay) will unavoidably become suspended and spilled during dredging operations in the channel and harbor areas, especially when using a backhoe dredger. The fine sediment plume created by the dredgers will increase water turbidity as it gets dispersed over significant distances by the relatively strong currents in the estuary (EIA 6.6.1.b, see summary in Table 6.66) and will eventually settle in sheltered regions of the project area (namely the coastal mangrove forest), even if dredging does not occur within 50 meters of the riverbank.

Nearby coral reefs at Parque Nacional Golfo de Chiriquí are at high risk of being impacted by fine suspended sediments transported away from the estuary by the ebb tide, if sediments settle on the reefs (Risk & Edinger 2011). Recent examples in Florida, USA demonstrate the extensive damage that dredging can have on reef systems (Miami Waterkeeper, 2017).

These impacts will persist over time as dredging of the navigational channel, turning basin and port areas extends over one year, followed by annual maintenance dredging of the navigational channel and associated sediment dumping in disposal areas after completion of project construction. Additionally, the designed Dredging Material Disposal Site is only 9 km away from the coral reefs at Parque Nacional Golfo de Chiriquí, which represents a significant risk of environmental impact on the reefs when fine sediments get stripped out during dumping operations and are then transported by the prevailing currents towards these sensitive areas, where they may eventually settle.

Therefore, it is strongly recommended that the dispersal and fate of fine sediments spilled during dredging and disposal operations be investigated in detail, ideally by use of numerical hydrodynamic models designed for simulating the dispersion of fine sediments.

3. Marine Traffic and Protected Areas

Developer's Claims:

- The project is not located within a protected area; the nearest UNESCO site, Coiba Island National Park, is 168 km away. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project)

- Navigation and dredging are permitted within the protected estuary according to the resolution establishing the protected area. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project)

- Ships will utilize existing sea lanes that do not cross any protected areas associated with UNESCO sites or Coiba Island. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project)

- The channel follows the natural thalweg of the tidal channel and Río Chiriquí Nuevo, with segments requiring no deepening. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project, EIS)

- An expected maximum of 1.7 vessels per day reduces collision risks with marine species; strict navigation regulations will be enforced. (Source: Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project, EIS)

- Humpback whales are located away from the navigation area east of Boca Brava, avoiding interference with shipping routes. (Clarifications to Sensitive Questions on the Puerto Barú Project, EIS)

Technical Assessment:

The closest straight-line distance from the navigational channel to Coiba Island National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (UNESCO, 2024), is approximately 63 km, not the 168 km stated by the developers. Additionally, the port facilities are near other critical protected areas and sensitive ecological areas. For example, the port facilities are only 12 km from Refugio de Vida Silvestre Playa la Barqueta Agrícola, 20 km from Parque Nacional Marino Golfo de Chiriquí, and 57 km from Refugio de Vida Silvestre Playa Boca Vieja. Given the project's proximity to these sensitive sites and the prevailing east-southeast ocean currents (Copernicus Programme, 2023), the EIS warrants a more thorough evaluation of potential environmental impacts on nearby protected areas.

As discussed in Section 2, dredging of the navigational channel and dumping at the disposal sites is expected to result in significant dispersion of fine sediments, which could affect water clarity and benthic habitats critical for coral reefs (Risk and Edinger, 2011) and sea turtles, both of which are found in high densities down current from the proposed dredging locations. Once the port becomes operational, it is highly likely that increased vessel traffic would negatively disrupt marine life through underwater noise pollution (Erbe et al., 2018), the potential for spills (Ketkar and Babu, 1997), and the increased likelihood of ship strikes (Bezamat et al., 2015), posing risks to resident species within and outside nearby protected areas.

Much of the EIS focuses on the impacts this port development would have on the proposed navigation channel, but this development would also impact the Gulf of Chiriquí itself, an important marine mammal area. As the Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force states:

“The Gulf of Chiriquí is identified as an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) indicating that the area is a critical habitat for breeding and feeding purposes to important biodiversity and merits prioritization for conservation measures by governments, environmental groups, and the public” (IUCN-MMPATF).

Observational data show that humpback whales, Bryde’s whales, hawksbill sea turtles, critically endangered Pacific smalltail sharks, common bottlenose dolphins, and the pantropical spotted dolphins inhabit the Gulf of Chiriquí, including areas near the proposed shipping routes. Moreover, numerous sightings of the endangered green sea turtle have been noted in areas closest to the proposed port facilities.

The assertion that marine mammals are absent from navigation areas contradicts data from sources like the Ocean Biogeographic Information System (OBIS-SEAMAP; Halpin et al., 2009). Even with a low estimated vessel density of 1.7 to 2.5 ships per day (EIS Executive Summary, p. 132), the cumulative risk of ship strikes remains a significant threat to migratory and resident species (Bezamat et al., 2015). The claim that marine mammals will not be affected by the port’s operations is not supported by sufficient evidence, and a more detailed impact assessment is needed to evaluate the true risks, particularly during migration and breeding seasons for sensitive species.

The developers claim that ships will utilize existing sea lanes to access the proposed navigation channel. While it’s true that sea lanes exist along the oceanic boundary of the Gulf of Chiriquí, these lanes do not extend into the gulf itself (Cerdeiro, 2020). In fact, the EIS proposes establishing new sea lanes to access the navigation channel to avoid marine mammal habitat, contradicting its own assertion.

The most effective method for reducing ship-whale strikes is to reduce their spatial overlap, followed by reducing vessel speeds (Cates et al., 2016). While the EIS provides preliminary plans for establishing a Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) and maximum vessel approach speeds in the Gulf of Chiriquí (EIS Section 7.2.1.2, Vulnerable aquatic species), the question of enforcing these measures remains to be seen. In assessing the compliance of ships to the TSS and speed limits introduced in 2014 in the Gulf of Panama, Guzman et al. (2020) highlight that while most vessels adhered to the TSS, compliance with speed limitations was poor (~19% of vessels in 2015 and less than 10% of vessels in 2016 adhered to restrictions).

Furthermore, even if most vessels adhere to the TSS, for this to be effective it would have to be established away from whale habitat to attenuate the risk of whale-vessel collisions. Humpback whale habitat extends from areas east of Boca Brava (as mentioned in the EIS) to just west of the Boca Brava strait (Guzman et al., 2020, Figure 1). Vessels would therefore necessarily have to cross humpback whale habitat in order to enter the navigation channel, diminishing the proposed reduction in ship-whale collision probability. It is therefore reasonable to assume that neither establishing a TSS nor implementing speed limitations would be sufficient measure to reduce the probability of ship-whale strikes.

Conclusions on Environmental Impacts and Claims

The Puerto Barú EIS, supporting documents, and other advertising material (such as the project website) present numerous claims that either lack sufficient evidence or misrepresent the potential impacts (and benefits) on critical ecosystems, including mangroves, coral reefs, and resident marine species.

Significant concerns exist regarding the exact methodology applied to the sediment transport modeling, the misrepresentation of proximity to key protected areas and the possible benefits of improved water circulation in the estuary, the inadequate assessment of increased marine traffic impacts on resident marine animals, and the general dismissive tone of the EIS to potential environmental risks in favor of the possible socioeconomic benefits of the port.

Our assessment calls into question some of the conclusions of the Puerto Barú EIS and the potential impacts on nearby protected areas, mangroves, coral reefs, and other local species, including those protected under Law 304 of May 31, 2022. Finally, while the EIS does acknowledge the potential for minimal impacts in some areas, the proposed mitigation strategies, particularly related to dredging operations, appear to be inadequate and unsupported by the best available science.

References

Aijaz, S., Driscoll, A., Sayce, A., Kaegaard, K., Klabbers, M., & Misra, S. (2013, January). Fine sediment transport modelling for design of port facilities. In Australasian Port and Harbour Conference (14th: 2013: Sydney, NSW) (pp. 1-6). Barton, ACT: Engineers Australia.

Alhaddad, S., Keetels, G., Mastbergen, D., van Rhee, C., Lee, C. H., Montellà, E. P., & Chauchat, J. (2024). Subaqueous dilative slope failure (breaching): Current understanding and future prospects. Advances in Water Resources, 104708.

Alongi, D. M. "The ecology of mangrove forests." Science 299, no. 5615 (2003): 1802-1804.

Alongi, D.M., (2002). Present state and future of the world’s mangrove forests. Environmental Conservation 29, 331-349.

Alongi, D. M. (2008). Mangrove forests: resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuarine, coastal and shelf science, 76(1), 1-13.

Alongi, D. (2009). The energetics of mangrove forests. Springer Science & Business Media.

Azeez, A., Muraleedharan, K.R., Revichandran, C., Sebin John Seena, G., Ravikumar C.N., Arya, K.S., Sudeesh, K. & Prabhakaran, M.P. (2022). Modelling of sediment plume associated with the capital dredging for sustainable mangrove ecosystem in the Old Mangalore Port, Karnataka, India. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 56, Elsevier.

Bernard, W.D., 1978. Prediction and control of dredged material dispersion around dredging and open-water pipeline disposal operations. Technical Report DS-7-13, Dredged Material Research Program. USWES, Environmental Laboratory, Vicksburg, USA

Bezamat, C., Wedekin, L. L., & Simões‐Lopes, P. C. (2015). Potential ship strikes and density of humpback whales in the Abrolhos Bank breeding ground, Brazil. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 25(5), 712-725.

Bridges, T.S., Ells, S., Hayes, D., Mount, D., Nadeau, S.C., Palermo, M.R., Patmont, C. & Schroeder, P. (2008). The Four Rs of Environmental Dredging: Resuspension, Release, Residual and Risk. USACE Environmental Laboratory report ERDC/EL TR-08-4.

Cates, Kelly & Demaster, Doug & Brownell, Robert & Gende, Scott & Ritter, Fabian & Panigada, Simon (2016). Strategic Plan to Mitigate the Impacts of Ship Strikes on Cetacean Populations: 2017-2020.

Cerdeiro, Komaromi, Liu and Saeed (2020). Data source: IMF's World Seaborne Trade monitoring system.

Chamberland-Fontaine, S., Heckadon-Moreno, S., & Hickey, G. M. (2022). Tangled Roots and Murky Waters: Piecing Together Panama's Mangrove Policy Puzzle. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 5, 818722.

Copernicus Programme. (2023). Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis: The cmems_mod_glo_phy_my_0.083deg climatology_P1M-m Product. EU Copernicus Marine Service.

Ellison, A.M., Farnsworth, E.J., 1993. Seedling survivorship, growth, and response to disturbance in Belizean mangal. American Journal of Botany 80,1137-1145.

Ellison, J. C. (1999). Impacts of sediment burial on mangroves. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37(8-12), 420-426.

Ellison, J.C. (2021). Factors Influencing Mangrove Ecosystems. In: Rastogi, R.P., Phulwaria, M., Gupta, D.K. (eds) Mangroves: Ecology, Biodiversity and Management. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978981-16-2494-0_4

Erbe, C., Dunlop, R., & Dolman, S. (2018). Effects of noise on marine mammals. Effects of anthropogenic noise on animals, 277-309.

Guzman, H., Hinojosa, N., and Kaiser, S. (2020). Ship’s compliance with a traffic separation scheme and speed limit in the Gulf of Panama and implications for the risk to humpback whales. Mar. Pol. 120:104113. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104113

Halpin, P.N., A.J. Read, E. Fujioka, B.D. Best, B. Donnelly, L.J. Hazen, C. Kot, K. Urian, E. LaBrecque, A. Dimatteo, J. Cleary, C. Good, L.B. Crowder, and K.D. Hyrenbach. 2009. OBIS-SEAMAP: The world data center for marine mammal, sea bird, and sea turtle distributions. Oceanography 22(2):104-115

He, Z., Yen, L., Huang, H., Wang, Z., Zhao, L., Chen, Z., ... & Peng, Y. (2022). Linkage between mangrove seedling colonization, sediment traits, and nitrogen input. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 793818.

IUCN-MMPATF, ‘Gulf of Chiriqui IMMA’, Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force (MMPATF) Website. Available at: https://www.marinemammalhabitat.org/factsheets/gulf-of-chiriqui-imma/ (Accessed:05.11.2024).

IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. (2023). Gulf of Chiriquí ISRA Factsheet. Available at: https://sharkrayareas.org/wp-content/uploads/isra-factsheets/12CentralSouthPacific/Gulf-of-Chiriqui-12CentralSouthPacific.pdf (Accessed:11.07.2024).

Ketkar, K. W., & Babu, A. J. G. (1997). An analysis of oil spills from vessel traffic accidents. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2(1), 35-41.

Lugo, A. E., & Snedaker, S. C. (1974). The ecology of mangroves. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 39-64.

Maiti, S. K., & Chowdhury, A. (2013). Effects of anthropogenic pollution on mangrove biodiversity: a review. Journal of Environmental Protection, 2013.

Ministerio de Ambiente de Panamá (2024). Informe Técnico Justificativo para la Definición de los Límites del Área de Recursos Manejados Manglares de Alanje, David y San Lorenzo. https://miambiente.gob.pa/consulta-publica-del-borrador-de-resolucion-ministerial-donde-se-adaptan-los-limites-de-los-manglares-de-alanje-david-y-san-lorenzo/

Ministerio de Ambiente de Panamá (2021). https://sinia.gob.pa/suelos/

Miami Waterkeeper. (2017, May 18). Explosive report finds PortMiami dredging caused extensive coral reef damage. Miami Waterkeeper. https://www.miamiwaterkeeper.org/explosive_report_finds_portmiami_dredging_caused_extensive_coral_reef_damage

Nardin, W., Vona, I., & Fagherazzi, S. (2021). Sediment deposition affects mangrove forests in the Mekong delta, Vietnam. Continental Shelf Research, 213, 104319.

Newsroom Panama. (2024, September 12). Environmental controversy involving the Puerto Barú project in David, Panama. https://newsroompanama.com/2024/09/12/environmental-controversy-involving-the-puerto-baru-project-in-david-panama/

NIRAS. Sediment Dispersion Modeling for Dredging Activities at Rosslare Europort - Appendix I. (2021)

Panama. (2022). Ley 304 del 31 de mayo de 2022, por la cual se reconoce la conservación de los arrecifes de coral y sus ecosistemas asociados como de interés público y se dictan otras disposiciones. Gaceta Oficial, No. 29548-A. Retrieved from https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/29548_A/91930.pdf

Risk, M. J., & Edinger, E. (2011). Impacts of sediment on coral reefs. Encyclopedia of modern coral reefs. Springer, Netherlands, 575-586.

Smith III, T. J. (1992). Forest structure. Tropical mangrove ecosystems, 41, 101-136.

Thampanya, U., Vermaat, J. E., & Terrados, J. (2002). The effect of increasing sediment accretion on the seedlings of three common Thai mangrove species. Aquatic Botany, 74(4), 315-325.

Truong, D. D., Tri, D. Q., & Don, N. C. (2021). The impact of waves and tidal currents on the sediment transport at the sea port. Civil Engineering Journal, 7(10), 1634-1649.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2024). Coiba National Park and its Special Zone of Marine Protection. Retrieved 2024 from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1138/

Van Rijn, L.C. (2023). Turbidity due to dredging and dumping of sediment. https://www.leovanrijn-sediment.com/

Warren, I. R., & Bach, H. (1992). MIKE 21: a modelling system for estuaries, coastal waters and seas. Environmental software, 7(4), 229-240.

Zárate, M. F. P. (2024). Aclaraciones a Interrogantes Sensitivas sobre el Proyecto Puerto Barú. https://puertobaru.com/proven-environmental-sustainability/